|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

The Dutch history canon: a never-ending debate?!

By Drs. H.K.J.

(Huub) Kurstjens, test developer for history and politics at CITO

(Institute for Test Development),

The well-known

Dutch historian Pieter Geyl (1887-1966)

argued at one time that history was ‘a

never-ending debate’. The same thing can be said about the ongoing

reform in Dutch history education. Traditionally a university degree

guaranteed the expertise of history teachers and henceforth the

level of history teaching. Half a century ago there was hardly any

disagreement about the historical curriculum, if at all.

Professional historians took an ‘implicit

canon’ for granted: they largely agreed upon the contents of

the curriculum with variations for each sociopolitical segment of

the population.[2]

Which developments in society and in history education called for an

‘explicit canon’? The fragmentation of history education

In present-day

Dutch history education, the concept of history has become

fragmented: the facts have lost their coherence and the main lines

have disappeared from view. This is due to rapid social changes,

far-reaching globalization, revised notions of history as well as

pressures from various emancipatory movements. The

political-institutional history of recent decades, presented

chronologically from a traditional Eurocentric perspective,

masculine and chauvinistic by nature, was no longer satisfactory.

Among other things, socio-economic history and the history of

changes in mentality were thought to deserve more space. Curricula

changed at a rapid pace and exam topics became evermore exotic.

Moreover, history education was increasingly used by interest groups

and defined by current events. Thus, more attention was demanded for

women’s history, environmental history, the history of

the Third World as well as the history of the integration of

At the same time

as thematic history teaching was introduced, more attention was

demanded for the teaching of historical skills. Mere knowledge would

not do; it was to serve a purpose. Historical knowledge combined

with historical skills was to be socially relevant and meaningful

and also preferably useful in other subjects. Another consideration

was that in our secularised and individualised country with its

heterogeneous population and with its traditional religious and

socio-political barriers removed, the sense of a shared identity was

increasingly at risk of disappearing. A common historical frame of

reference might help solve the identity crisis from which the nation

suffered. In other words, it was time for the teaching of a survey

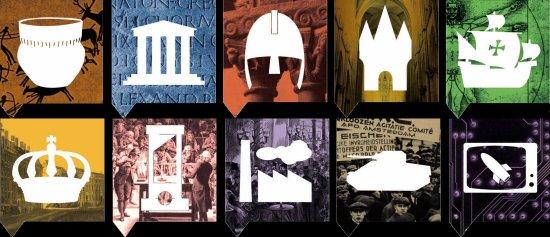

of historical facts. The ten historical periods defined by the De

Rooy committee

The De Rooy

committee, so called after its president,

Students are

first introduced to this system in primary education (pupils up to

12 years of age), re-acquainting themselves with the periods during

the first stage of secondary education (age groups 12 to 14) and

once again during the second stage of secondary education (age

groups 14 to 17/18). The underlying idea is that repeating a period

once more, the description of a period, in combination with an icon,

will cause the subject matter to sink in properly. The best way of

promoting historical awareness is to use a variety of approaches and

skills as well as a frame of reference simultaneously and in mutual

relationship.

According to the

committee, it will be easier for students to master the frequently

difficult and dry subject matter by building on what was learnt at

an earlier stage. It is stated specifically, however, that students

are not meant to learn isolated facts like dates and personal names

by heart. This is not thought useful. Such matters are valuable only

if they contribute to the orientation process by helping to clarify

general, distinctive aspects of a particular period. Consequently,

the committee abstained from including lists of events, persons etc.

Moreover, the committee argued, any selection would be

indiscriminate and arbitrary. To be sure, the general characteristic

features of a period ought to be presented graphically, but

without any specific illustrations being supplied. In this way,

one student can memorise knowledge of the Reformation by reference

to Luther or Calvin and another by reference to Zwingli, Erasmus or

other reformers. The illustrations are just steppingstones to be

used in learning something general about a particular period, no

more and no less. By now, this approach has been accepted by Dutch

parliament and the Ministry of

Education and turned into an act for primary education and

the first stage of secondary education. For the second stage of

secondary education this approach is to result in reformed centrally

organized final examinations within a few years from now. The periods censured

The

recommendations published by the De Rooy Committee met with quite

some censure. The division into ten periods might benefit the

teaching method, but received a great deal of scholarly objection.

Many historians judged it to be outright arbitrary, even

unacceptable. If this protest could be disregarded with a view to

the supposed benefit to students trying to master the subject

matter, particularly since other divisions into periods continued to

be used as well, the distinguishing features were another matter

entirely. Were they really typical of the period under review, were

they consistent and of the same order? Would this division allow

treating longitudinal developments? And was it really true to say

that it did not matter which specific illustration was used to

characterize a period? Did Columbus and Luther not illustrate the

period of discoverers and reformers (1500-1600) better than

Olivier van Noort or Johannes Hus? And did the

emphasis on Western-European history not occasion eurocentrism with

the added risk of stereotyping:

‘history written by white males’, which was to reinforce the

national identity into the bargain? How, for example, were Turkish

and Moroccan children to identify with such a distant history and

world view that was clearly not theirs? The canon as proposed by the Van Oostrom Committee

What was missing

in particular became apparent from a report published in January

2005 by the Education Council, the most important advisory body to

the Ministry of Education. It stated that too little attention had

been paid to a ‘canon’ that expressed the Dutch identity. According

to the Education Council essential elements in this respect are

‘those valuable components of our culture and history that we wish

to pass on to later generations by means of education. The canon is

of importance to the whole of society, not just to an elite group’.[3]

Such a canon might underpin education’s socializing task, especially

considering the existing integration problems. With so many children

of foreign descent, the Council argued, one had better see to it

that Dutch culture and history were tranferred properly. These

recommendations were, of course, not to be dissociated from the

social unrest resulting from two prominent Dutchmen being murdered,

the politician Pim Fortuyn in May 2002 and the film director Theo

van Gogh in November 2004. The Duch nation was at risk of polarising

at a fast rate: social tensions were running high.

The Minister of

Education at the time was convinced that ‘if young people in the

The Van Oostrom Committee –

so called after its president Prof. Dr. F.P. van Oostrom of The canon: appearance, essence and contentsAppearance

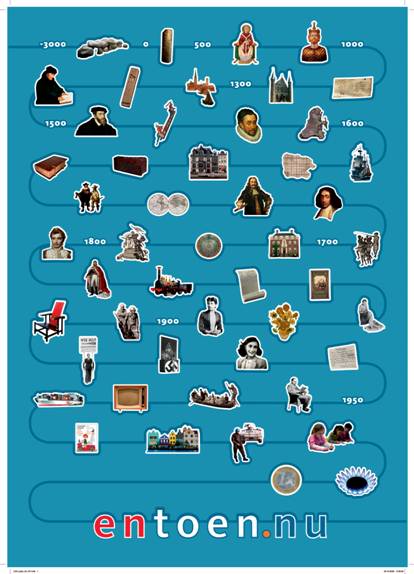

The canon has

been presented visually on a chart, as a poster, as well as on the

canon website.[7]

The canon as presented consists of a series of 50 ‘windows’,

arranged chronologically on a time line (figure 2).

(figure 2) The main function of the chart is that of a teaching aid: imprinting the canon’s images (and their sequence in time) and exciting the students’ curiosity and imagination. The chart is meant to remain hanging on the classroom wall, clearly visible at all times, to serve as point of reference for lessons that pertain to the canon. The canon consists of four layers: first, and consecutively, one of the 50 windows is presented together with an accompanying short Story explaining the significance to be attached to this particular component of the canon. Next, the possibilities for educational extension are enumerated, the Branches so called (these are suggestions for themes that can be adopted to extend a view from the window or studied in depth). To these branches two more subdivisions have been added: The present and the past and Inside the treasury. The former contains suggestions for comparing past and present, the latter for filling up the treasury (a box of educational objects) with elements that make the past ‘tangible’. Finally, there are the References. They supply further information about a subject (among which suggestions for excursions, for relevant literature and websites).

essence

The committee

has opted for a cross-curricular canon. This implies the possibility

of establishing connections between subjects such as Dutch,

geography, history and culture and the arts. The canon would have to

be presented twice in the course of a school career: once in the

upper stage of primary education (age groups 8-12) and one more time

in the first stage of secondary education (age groups12-14/15). The

positive effect of revision and recognition would, as students grow

older, have to be combined with treatment in depth and enrichment of

the 50 windows. For primary education this means: treatment in a

concrete and narrative fashion with the use of icons that give

students something to hold on to, clear beacons in time (no pumping

dates into heads, however!), appealing, inviting (a canon that is

‘alive’) and close to home (with narratives about The Netherlands,

but also with opportunities to link up with the local canon). For

secondary education one could think of enlarging, expanding and

enriching materials, studying these in depth, establishing more

interrelations, paying more attention to abstract subjects and

processes, to political and economic history, the foreign cultural

canon, to art suitable for ‘more mature youths’ and to individual

characters and groups.

contents

The subjects

included in the canon passed a strict selection. As a result, the

subjects can be given their due, and at the same time undue

proliferation is prevented. The most important challenge is not so

much whether or not the subjects are treated (they occur in most

textbooks anyhow), but how they are treated. They should

function as stepping-stones for a lifetime of learning and

experiencing things. With this approach thematic teaching has

returned, with a difference: the themes are now part of a national

framework. The canon censured and defended

Hardly had the Van Oostrom Committee published its report when the canon, too, met, not only with approval, but with a great deal of criticism, especially from academics and teachers. In summary the negative comments were these:

The canon was defended on these grounds:

The current

state of affairs

From the publication of ‘The Dutch Canon’ and the comments it received it is clear that historical knowledge needs to be paid more attention to in schools and teacher training institutes. The proposal received a lot of coverage in the national press and in spite of the negative criticism mentioned above, it was welcomed with great enthousiasm by large sections of society. The following factors aroused this enthousiasm:

The report on the canon advocates raising the quality of teacher training courses and raising the level of knowledge and instructional skills of teachers. The publication of the canon may well contribute to solving the problem of the erosion of subject knowledge. The canon itself, however, occasions another problem. The curricula for primary as well as secondary education were required to include the ‘ten historical periods’ as laid down quite recently by the De Rooy Committee. These ten historical periods aim to define, as does the canon, a core of historical knowledge. The former defines it in terms of ‘characteristic aspects’ of the periods. These amount to 49 features such as ‘the industrial revolution’ or ‘imperialism’ for the 19th century, and ‘the years of crisis’ or ‘the Cold War’ for the 20th century. The attainment targets[10] use these general characteristics and do not specify any facts. Selecting specific facts can be left to schools and teachers, the committee argued. They are free to select either Dutch or non-Dutch illustrations. The outline of ten periods does not specify which historical facts students ought to know, whereas the ‘ Dutch Canon’ does lay down specific facts. These could serve to illustrate the general characteristics of the ten historical periods of the De Rooy Committee. No problem then, one might think. However, the 50 canon windows do not match the 49 features in De Rooy. For some features there are various illustrations, for others there are none at all. Moreover, some items in the canon cannot be subsumed under any of the distinctive features. According to critics, the canon is nothing more than a rambling series of facts with hardly any coherence in time. Indeed, that is what the canon poster shows: a long, winding time line without any marked periods. This will not help develop historical and chronological awareness, a key objective in the ten periods of De Rooy. For this reason, the canon poster was critized severely by educationalists (also because the time line takes alternate turns from left to right and right to left). Then, the feature of the 50 windows does not merely suggest content; it also suggests a teaching method: take these 50 windows as starting-points, they constitute a principle for a methodical arrangement. The ten periods of De Rooy suggest, however: start from the periods and their features, and find illustrations for them – e.g. in the canon. As a result, the actual practice of teaching history is at risk of having to cope with the tangle of two different systematic principles and methods. The uncertainty this creates for schools, training institutes and educational publishers is already quite apparent. Using the canon as sole principle is no solution, as it deals exclusively with The Netherlands. It would not do for the final examinations in secondary education to limit the subject matter to Dutch history. The ten periods do offer the opportunity to include international history. Concluding

remark

At the moment of writing,

the possibility of merging the specific illustrations of the canon

and the ten periods is being considered; it is hoped that the two

approaches will reinforce each other and produce a synergetic

effect. It might give rise to a comprehensive and coherent national

history curriculum. Another possibility is to use the specific

illustrations in the canon as starting-points in primary education

and the more abstract features of the ten periods in secondary

education. Whether or not the canon and the periods can really be

merged or attuned in this way remains to be seen. At the time of

going to press, this was not yet known. Summary: (June 7, 2007)

Literature and

websites:

- ‘Verleden, heden en toekomst’; the report of the Committee of

historical and social education (under the chairmanship of Prof. Dr.

P. de Rooy), Enschede 2001.

- IVGD (Netherlands

Institute for Teaching and Learning History); (for the Dutch

version, see:

http://www.ivgd.nl/indexnl.htm; for the English one, see:

http://www.ivgd.nl/indexen.htm). Some quotations at the end of

this article have been taken from a letter of advice from IVGD,

referring to a report of the canon-committee of april 2007: ‘Canon

en geschiedenisonderwijs - het probleem en de oplossing'.

- De stand van educatief

- entoen.nu, de canon van Nederland; the report of the committee of

development of the Dutch canon (under the chairmanship of Prof. Dr.

F. P. van Oostrom), The Hague 2006; (For the Dutch version, see:

www.entoen.nu;

for the English one, see:

http://www.entoen.nu/default.aspx?lan=e).

- M. Grever, E. Jonker, K. Ribbens en S. Stuurman; Controversies

around the canon, Assen 2006.

- Kleio, magazine of the association of History teachers in the - Cito, Institute for Test Development; Cito is one of the world’s leading testing and assessment companies. Measuring and monitoring human potential has been its core competence since 1968; (for the Dutch version, see: http://www.citogroep.nl/index.htm; for the English one, see: http://www.citogroep.nl/com_index.htm).

Summary:

Due to several

causes the concept of history has become fragmented in Dutch history

education in the last decades. At the same time more attention was

demanded for the teaching of historical skills. Historical knowledge

combined with historical skills was to be socially relevant and

meaningful. Moreover the sense of a shared identity was increasingly

at risk of disappearing and a common historical frame of reference

might help solve the identity crisis from which the

Curriculum Vitae:

Mr Kurstjens (1956) studied History and Geography at the teacher

training

In 1993 he started working at CITO (Institute for Test Development

in the

In his free time, Mr. Kurstjens is member of the board of the

Comitato Dante Alighieri of

[1] With thanks to Stefan Boom and Willem Kurstjens for their comments concerning content and style and with thanks to Jan Mets for the translation into English. [2] Until the late twentieth century the Dutch population was characterized by the segmentation into a number of strictly separated religious (catholic and protestant) as well as political (socialistic and liberal) groups. Each of these segments had its own organizations, press, schools, radio and television channels, labour unions etc. [3] The condition of Dutch education; a report by the Education Council (The Hague 2005), p. 13 [4] As mentioned in the letter of commission to the board for the Development of a Dutch Canon (May 26, 2005, p. 2), addressed to its president Prof. Dr. F.P. van Oostrom. [5] Boulahrouz is a famous Dutch soccer player of Moroccan descent; Beatrix is queen of The Netherlands.

[6]

The Dutch canon, part A, pp

[7]

For the Dutch version, see:

www.entoen.nu;

for the English one, see:

http://www.entoen.nu/default.aspx?lan=e.

[8]

This description was given by Prof. Willem Frijhoff,

professor of

contemporary (cultural) history in the Free University of

Amsterdam. To him must also be attributed this statement:

‘national integration can be declared successful as soon as

a Turkish or Moroccan immigrant or a descendant considers

William of Orange as the founding-father of his home

country.’ (In:

Geschiedenis Magazine, nr. 1, Jan-Feb 2007, p. 45). [9] Quote taken from an article by the Dutch writer of Moroccan descent Abdelkader Benali (Volkskrant of Saturday, October 21, 2006). [10] Attainment targets are minimum goals for knowledge, insight, skills and attitudes which the educational authorities deem necessary and achievable for a particular student population.

|

|||||||||